Ten weeks at the motherhouse in Rome – a grace. Ten weeks at the motherhouse in Rome working in the general archives – a gift. Ten weeks in Rome digitizing the letters of Saint Madeleine Sophie – priceless!

I was asked by the General Council to go to Rome this summer for two reasons: to be a companion to Margaret Phelan, RSCJ, when the rest of the community left for retreat, language school, vacation, the Canadian Assembly, the meeting of the Latin American provincials, etc. and, at the same time, to work in the general archives.

I had previously gone to Rome in 2009 when preparations for the renovation of the archives at the Villa Lante began. At that time, I had the delightful job of making an inventory of the hundreds of items in the museum and carefully wrapping and packing them away. Among them were the many items used by Sophie, her famous hat, her mittens, her veil and my favorite object, her couvert de voyage. It resembled a very large pocket knife and opened up into a spoon, a fork, a knife and a corkscrew. I also had the privilege of digitizing the originals of the 151 letters of Philippine to Bishop Rosati.

This summer, because another room of the archives space at the Villa was being renovated, Sister Phelan and her staff set up their computers, printer and scanner in the basement of the motherhouse. Sister Phelan and I did not have to take the tram to Largo Argentina and walk through the Trastevere (something I actually missed); we simply walked downstairs. About once a week we drove to the Villa to return boxes of documents, pick up others and check on the progress of the work being done.

My task this summer was to begin the work of digitizing the originals of the 14,000 or so letters of St. Madeleine Sophie Barat. The first letter in the collection is dated 1805 and the last a few days before her death in 1865. I was given the 1,200 letters to Eugénie de Gramont, the largest number in the collection. I was surprised at the number. When they were apart, Sophie wrote to Eugénie almost every day and was troubled if she did not receive a letter in return. It was helpful to read in Sister Phil Kilroy’s life of Sophie that Eugénie was her “support and consolation in countless difficulties” and that, on the other hand, “Eugénie needed Sophie because her friendship gave her a sense of inclusion in the Society of the Sacred Heart, especially following her previous stance (i.e., against Sophie and with Saint-Estève) in Amiens.” I completed work on only 220 of the letters – some one page, some six pages. Sister Phelan estimates that the project will take five years.

For the most part, Sophie’s letters are well preserved. In the 1800’s, fiber crops such as flax or cotton from rags were the primary materials for paper. Since the turn of the twentieth century, most paper is made from wood pulp and turns yellow, becomes brittle and deteriorates over time. It was the ink used in Sophie’s day that created a bit of a problem. It was iron gall ink which, in some letters, has eaten through the paper or has faded so much as to be almost invisible. In addition, the paper was sometimes very thin with writing on both sides. However, my difficulty in reading the letters was the fault of Sophie herself! Her handwriting is not easy to read and, if she was pressed for time, her penmanship became even more impossible to decipher. If she ran out of space at the end of the letter, she filled up the margins and not in any particular order!

The scanning program I used was more sophisticated than what I use in our archives and allowed me to enhance the image. It took a good deal of patience and was rather hard on my eyes, but it was amazing what I was able to do. In a few instances, the image that was nearly invisible to the naked eye could be read.

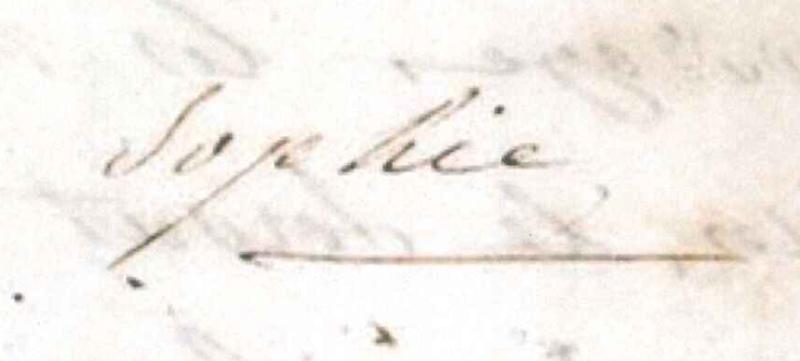

But the priceless part of my task was reading the letters after downloading them to an electronic file. I discovered that Sophie had pet names for her daughters. She called Eugénie “ma petite rate.” I didn’t find being called a female rat very endearing, but Phil Kilroy assured me that it was. I also turned to Sister Kilroy to ask about the name Sophie used for herself when ending her letters to Eugénie. She signed herself “votre petite merotte.” Merotte was not in any French dictionary but Sister Kilroy knew that it was a diminutive of mère.I have never been happy with Sophie’s signing of her name as “Barat” – even to her closest friends. So my joy was great when, along about 1830, she began to sign her name “Sophie.”

Mary Lou Gavan, RSCJ