Acknowledgement

“To focus on the on-going issue of racism in the world and the Society of the Sacred Heart’s participation in the historic sin of slavery ... we commit ourselves to recover the story of slavery in our early days in this country, to share this historical fact as widely as needed, to assist in the attempt to locate the descendants of enslaved persons who lived on property owned by the Society of the Sacred Heart, and to take appropriate steps to address this painful chapter in our history while also working to help transform on-going racist attitudes and behaviors." — Mandate of the Committee on Slavery, Accountability and Reconciliation

Acknowledging our participation in the structural sin of racism publicly became an element to mark the Society’s presence in North America for 200 years in 2018. (Watch Former Provincial Sheila Hammond, RSCJ, Welcome | Grand Coteau Gathering September 2018)

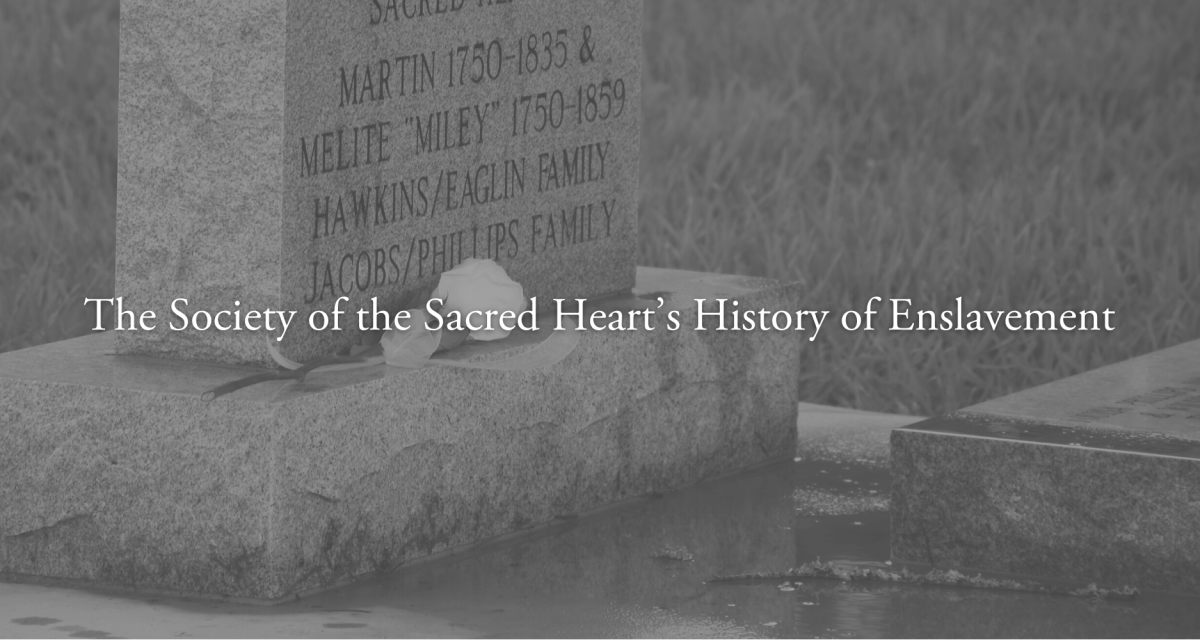

Claiming the truth of our past

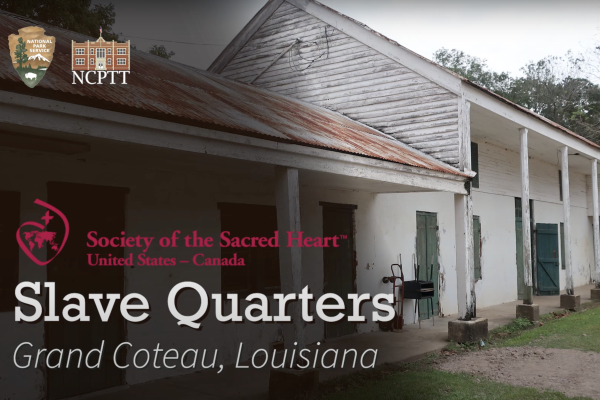

The communities of the Religious of the Sacred Heart (RSCJ), from the time of Saint Rose Philippine Duchesne (1818) until the close of the Civil War, participated in the violence of slavery by buying*, selling* and holding in bondage more than 100 men, women and children in the states of Louisiana, Missouri and Kansas. These individuals' skills were used and exploited to construct the buildings, make the bricks, and sustain the very foundations of the Society. They also shouldered much of the burden of the household labor, cooking, washing, gardening, and caring for the children in the schools.

The Society of the Sacred Heart’s first foundations:

- St. Charles, Missouri (1818 and closed 1 year later)

- Florissant, Missouri (1819)

- Grand Coteau, Louisiana (1821)

- St. Michael's, Louisiana (1825)

- St. Louis, Missouri (1827)

- St. Charles reopened (1828)

- La Fourche, Louisiana (1828)

- Sugar Creek, Kansas (1841) moved to St. Mary's, Kansas (1848)

- Natchitoches, Louisiana (1847)

The research shows that from the founding of the first schools until 1865, the Society enslaved approximately 150 people in Louisiana, Missouri and Kansas. The Society continues to conduct research in this area.

*We have opted to tell the truth about human chattel slavery clearly, here, by retaining the dehumanizing transactional language of the historical documents. However, we have chosen to call the reader’s attention to these terms with an asterisk. We hope the reader will trip over these terms while reading, and feel the discomfort of using them. Our intention is to make it clear that, although our historical documents may describe a person as being “gifted,” “loaned,” “bought,” or “sold,” we cannot unquestioningly accept such language today, because we cannot morally accept the premise of ownership and domination on which that language is based.