A note before reading

We offer reflection questions as an accompaniment to an individual or collective reading of this material. You are encouraged to use these questions to deepen your reading and prayer and to help direct your individual or collective reflection.

In March 1827, Bishop Rosati asked Rose Philippine Duchesne to take over the school and to accept the three Loretto Sisters into the Society of the Sacred Heart, which they were said to desire. Philippine wrote to her superior, Madeleine Sophie Barat, in June about the possibility of the Religious of the Sacred Heart taking over the school in Lafourche, and how the addition of English speaking nuns would benefit the Society [Callan SSHNA, pp. 166-168]. In her letter, Philippine weighs the cost of sending additional RSCJ to Lafourche against the cost of purchasing* an enslaved woman to work there:

Their travel would cost much less than the purchase of a single Negress. Me Xavier [Anna Murphy] tells me that if she purchases one, she will not be able to send anything, and I counted on her for our buildings. Besides other advantages of having only sisters in the house, a single Negress will cost 2,000 francs, and the travel of two sisters 1,000 or 1,500 francs.” [Philippine Duchesne to Sophie Barat, January 3, 1828]

In 1828 the Society took over the school with Mother Hélène Dutour, RSCJ, as superior, and former Loretto Sisters Regina Cloney and Rose Elder as novices who remained at Lafourche (Joanna Miles did not remain). They were joined a year later by Julie Bazire and Thérèse Detchemendy, RSCJ. From the beginning, there was controversy about the foundation’s proximity to and competition with St. Michael’s. The Society withdrew in 1832.

The 1830 census for Lafourche shows, listed under the name “Hellen Dutour,” 63 free white persons and three enslaved females: an adult woman, a child, and a teenager, who may have been mother and daughters. Other than the unnamed and possibly leased* cook working there in 1828 before the Society of the Sacred Heart arrived, this is the only document that shows the presence of enslaved workers at Lafourche, and no other record of them survives.

Sophie wrote to Philippine on 3 February 1832 about her “desire to close La Fourche convent, being utterly unable to furnish the necessary money and nuns.” Mother Duchesne informed Bishop de Neckere in New Orleans and the school closed in March. The students were sent home and the orphans to St. Michael’s, where other orphans were cared for. The RSCJ went to the house in Grand Coteau. [Callan SSHNA, p. 179]

Loretto Sister Joanna Miles, upon leaving Lafourche, traveled to St. Louis to begin a novitiate at Florissant, but soon left. Regina Cloney and Rose Elder went to Grand Coteau with the other RSCJ, where they died in 1835 and 1836. The property was returned to the Diocese of New Orleans and taken over by the Sisters of Mount Carmel from France in December 1833, but with only two Carmelites there, the school was soon closed. The buildings burned in 1855. [Callan SSHNA, pp. 179-180] There is no record of where the enslaved women went.

Natchitoches

In 1847, in answer to requests from alumnae of Sacred Heart schools, an academy was opened in Natchitoches, Louisiana. Most of the people known to be enslaved by the RSCJ in Natchitoches were members of the Jackson family who were previously enslaved by the Buard family, of which Catherine Felicie Buard, RSCJ (1826-1861), was a member.

At the time of the 1850 census there were two people listed as enslaved at Natchitoches; these are presumed (by reference to other contemporary documents) to be Jaco (/Jacquet, /Jacob, later called Bartholomew Jackson), a man of about 50; and a young woman named Adeline, around age 23 or so. Jaco appears in a Buard will along with his mother Françoise, born about 1781, and his grandmother Jeanne, born about 1757 (Louisiana, .S., Records of Enslaved People, 1719-1820). In 1855, Louisa, Jaco’s wife, and her children Odin (/Dan, /Daniel), Seraphine (/Sarah), Stanislaus, and Mitchell (/Jack), came to join him at Natchitoches, sent there as a legacy* to Sister Buard after the death of her brother, their slaveholder.

Amélie Jouve, RSCJ, made an official visit to Natchitoches as superior vicar in March 1859 and recommended that Jaco and his family be sold, except for Stanislaus, who she recommended to be sent to St. Michael’s. This document indicates that Jaco was singled out for sale because he had expressed a desire to purchase his freedom; perhaps as a result, she perceived him as having a “bad attitude.” [Memorial of visit, 1859; USCA]. However, in the 1860 Slave Schedule, it appears that the family remained unsold, despite Mother Jouve directing the superior to do so two years before. The Schedule, compiled in August, lists several people enslaved at Natchitoches: one male, 58 (presumably Bartholomew), one female, 40 (Louise), one female, 26 (Adeline), one female, 20 (Seraphine), one female, 18 (unknown), one boy, 12 (Stanislaus), one boy, 10 (Jack/Mitchell), one girl, 3 (Josephine), and one boy, 3 (Martin). (Although listed as female, it is possible Odin is the 18 year old indicated here.) The 1860 United States census for Natchitoches names Adeline Guinard as the superior and Catherine Thiéfry as assistant, with 17 RSCJ, seven of whom, listed as “servants," would have been coadjutrix sisters.

Later depositions of both Seraphine and Mitchell in 1910 indicate that sometime around 1860, their brother Stanislaus went to St. Michael’s to be trained as a carpenter, but the rest of the family stayed in Natchitoches. There is no mention of anyone being sold. However, Stanislaus’ mother and one or two siblings may have accompanied him. He appears as a baptism sponsor in 1862, as does a “Louisa,” who might have been his mother. On 20 February 1862, Father J. Boë writes in the baptismal register of St. Michael’s convent, “I baptized Mary Sarah daughter of Elisabeth and Adam servants of the Religious of the Sacred Heart. The godfather was Stanislaus, the godmother was Louisa, also servants.” [Baptismal Register, USCA]

The purpose of Seraphine and Mitchell’s 1910 depositions was to grant a pension due to Stanislaus for his service in the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War. (He and two others, his brother Martin and another man, ran away from St. Michael’s to join up.)

The Jackson family has many descendants. In the family’s oral history, there is a recollection of their ancestors being held in slavery by a Buard before being sold* to the Society, and they remember that Stanislaus was transferred to St. Michael’s shortly before the war to be trained as a carpenter, a skill which he later used to support his family. Family history also recalls a provision made at the time of sale* that the Society agreed to free the children when they reached age 30. Society documents do not record such a provision, but if this were intended, the end of the war - and therefore, the end of chattel slavery - arrived before the promise could be tested.

In January 1861, Louisiana seceded from the Union. The Union quickly moved to capture the important port of New Orleans. By April 1862, New Orleans fell, and by May, the ironclad Union gunboats had moved upriver and were docked at the wharf of St. Michael’s. Fighting and destruction came close to the foundation in Natchitoches.

After the war, the Jackson family from Natchitoches appears to have been divided between that town and New Orleans. Louisa and her children, Odin and Josephine, and their families remained well into the 20th century in Natchitoches. Stanislaus, Mitchell and Seraphine settled in New Orleans, where their family continued to live for several generations. According to the family’s oral history, Mitchell found occupation as a boat pilot, and Stanislaus was involved with the construction of the levees in New Orleans.

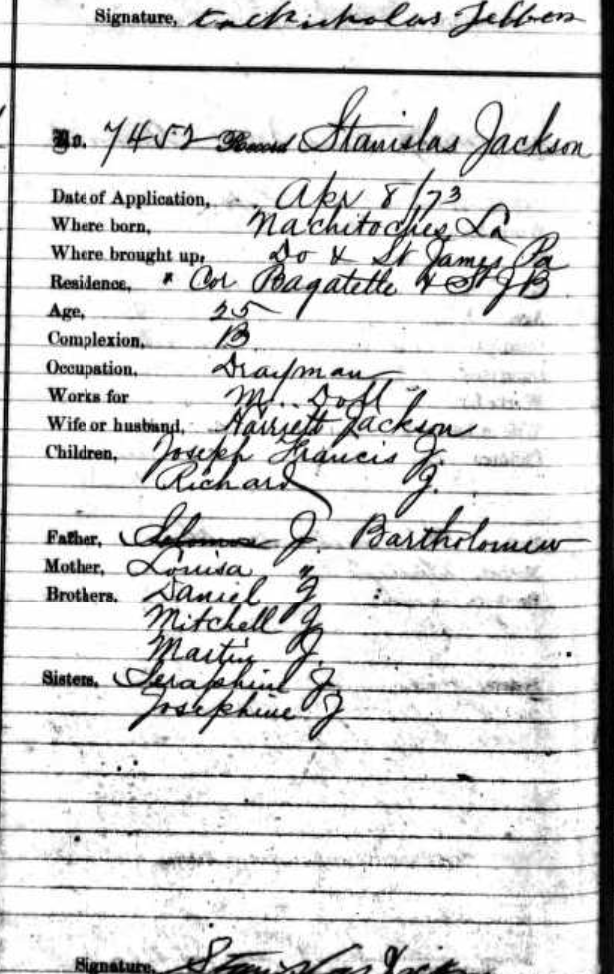

An application for an account from the Freedmen’s Bank files for Stanislaus Jackson on April 8, 1873 (shown above) lists the following:

Where born: Natchitoches, LA

Where brought up: Same & St. James Parish

Residence: Cor. Bagatelle & St. J B (now Pauger and North Robertson in New Orleans)

Age: 25

Occupation: Draftsman

Works for M. Doll

Wife: Harriet Jackson

Children: Joseph, Francis, Richard

Father: Bartholomew; Mother: Louisa

Brothers: Daniel, Mitchell, Martin

Sisters: Seraphine, Josephine

It is signed by Stanislaus Jackson.

It does not appear that any of the formerly enslaved population remained on the Natchitoches property after the war, as the 1870 Natchitoches Census lists only nineteen RSCJ with Mathilda Doremus as superior, ten teachers and nine domestic servants (coadjutrix sisters), eight born in Ireland and one in Germany. Eighteen students are named. All are listed as white females.

By 1874, fully half of the twenty students enrolled in the academy were not Catholic. Mother Susannah Boudreaux notified Bishop Martin, a devoted friend of the convent, of their intention to withdraw, which was a great suffering for him. The bishop died in September 1875 and early the following year, Mother Crescence Alschner closed the convent there and the small group took a steamboat for St. Michael’s. [Callan SSHNA, pp. 550-551]. Fifteen names on a marble slab next to Immaculate Conception Cathedral commemorate the RSCJ who died at Natchitoches. Today the former Academy property is part of the campus of Northwestern State University.

Researched and written by Emory Webre and Maureen Chicoine, RSCJ.

References

Callan SSHNA. Louise Callan, RSCJ, The Society of the Sacred Heart in North America. London, New York, Toronto: Longmans Green, 1937

Minogue, Anna C. Loretto: Annals of the Century. New York: America Press, 1912

USCA. United States-Canada Archives, Society of the Sacred Heart, St. Louis, Missouri

Louisiana, U.S., Records of Enslaved People, 1719-1820, Gwendolyn Midio Hall. Ancestry.com Operations, Inc.