A note before reading

We offer reflection questions as an accompaniment to an individual or collective reading of this material. You are encouraged to use these questions to deepen your reading and prayer and to help direct your individual or collective reflection.

In 1834, Mother Audé was recalled to Rome. Julie Bazire, RSCJ, became the superior with Aloysia Hardey, RSCJ, as assistant. All three are listed as slaveholders in sacramental registers under the names Mme. Eugenie Audé, Mme. Julie Basare/Bazare (Bazire), and Mme. Aloysia Hardey.

Seven legal documents detail the purchase* of 21 enslaved persons by the convent between the years of 1837 and 1856. These include the following names:

- 11 January 1837: Julie Bazire purchased* Darky (31), Washington (12), John (9), Eliza (9 months), Henry (26), John (9), Joseph (6), and Mary (2)

- 30 April 1838: Aloysia Hardey purchased* Rosalie (10+)

- 13 May 1848: Maria Cutts purchased* husband and wife Baker (26) and Ann (20, designated in the document as “mulatta”), along with Joseph (4) and Mary (14 months), presumably their children

- 5 May 1856: Marguerite Amélie Jouve purchased* Maria (23)

A record dated May 1837 also exists of the convent’s sale* of an elderly woman, Françoise, for $100 to a person named Celestin, who purchases Françoise for the purpose of freeing her. The sale is granted by Mother Hardey because of Françoise’s advanced age and the “lovable intentions of Celestin.”

An inventory written about 1849 also lists some names (but appears to have some errors).

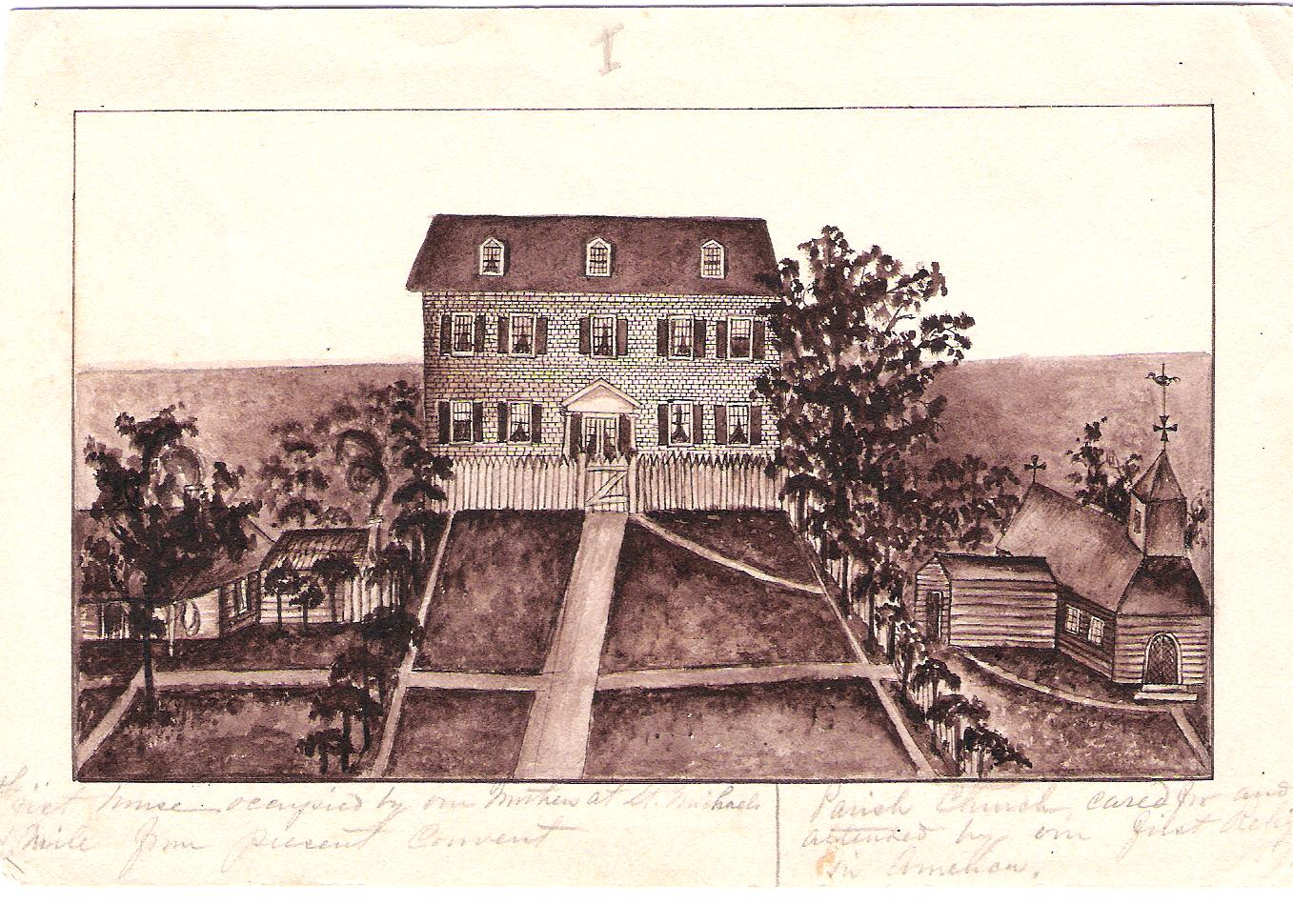

By the time of the 1840 census, there were a total of 27 enslaved men, women and children listed as living at St. Michael’s, a number augmented by the religious purchasing* additional people, and by the births of children to the couples enslaved there. Their need for labor also increased in that period due to the rapid growth of the school to 200 students and an on-site orphanage which had grown by then to 60 children; a large three-story building was also built in 1848 in Convent, undoubtedly constructed with the labor of at least some of these 27 individuals. In the 1840’s, the names of 12 enslaved persons appear in records for whom there are no acquisition* records. The U.S. Slave Schedule for St. James Parish records 28 enslaved persons at St. Michael’s in 1850.

Between 1850 and 1860, the house journal at St. Michael’s has records of enslaved persons participating in the sacraments, processions, and devotions at the school. The St. Michael’s Convent baptismal register has seven entries of baptisms of enslaved persons, in addition to records of three marriages and two deaths. St. Michael’s Parish Church sacramental records contain records of 17 baptisms of persons enslaved by the RSCJ, in addition to two marriages and ten burials from the church.

By 1860, according to the U.S. Slave Schedule, there were 30 people enslaved at the “Convent St. Michael.” One of these is a man named Washington (likely the same Washington Spaulding who was purchased* by the convent in 1837 with his mother and siblings at age 12), who is described in a letter in 1857 as “the mulatto who always waited on table” during the bishop’s visits, and who the letter’s author speculates may have been the convent’s treasurer. Sometime after 1860, Stanislaus Jackson, son of Jaco and Louisa Jackson at Natchitoches, was sent to St. Michael’s to be trained as a carpenter. His mother and perhaps at least one or two siblings might have accompanied him. He appears as a baptism sponsor in a 1862 record there, as does a “Louisa,” who might have been his mother. (More on his family in the narrative of Natchitoches.)

Father Claude Tholomier, the pastor of St. Michael's Church in Convent, Louisiana, was apparently in the habit of giving instructions to the sisters there. In a letter that Mother Anna Shannon writes to Archbishop Blanc in New Orleans on December 6, 1857, she complains about several of the issues he raised at one of his visits, faulting her for the rules she had for the enslaved workers.

In her letter, Mother Shannon asks the Archbishop whether she should forbid the “negroes” to work or dance on Sunday, and whether the Archbishop instructed Father Tholomier not to give benediction to them if they make noise in church? She insists that she does forbid them from selling things on Sunday or to “play for balls at Mr. Landry's.” On Sundays, she states, she requires them to go to Mass in the convent chapel, also to attend catechism and night prayers.

She goes on to say that, while she is willing to submit to the Archbishop's requirements, she does not know how she will be able to keep them shut up all day. If they would go to other plantations on Sunday, she worries, they will engage in activities that would be worse than just work. [Archdiocese of New Orleans Collection (ANO), CANO-VI-l-m-1857-1206.pdf, University of Notre Dame Archives (UNDA), Notre Dame, Indiana 46556].

The letter demonstrates Mother Shannon’s interest in allowing some limited freedoms for the enslaved people at St. Michael’s on Sundays. Some of the enslaved individuals on Southern plantations might have had religious services outside of Catholic Mass where they would dance, sing and shout. They might even have been bringing these into their attendance at Catholic services (perhaps the “noise” she discusses). Since most of the enslaved individuals at the convent were baptized, she assured the Archbishop that she had them fulfilling their religious duties.

As the possibility of war loomed, the St. Michael’s superior, Mother Shannon assured the superior general, Madeleine Sophie Barat in Paris, of the loyalty of the enslaved persons on their site. “The Negroes work well and are peaceful and content.” A comment in the house journal notes that “Our Negroes continue to give us much consolation by their piety and industry. Their yearly holiday is a great event, but they always wish to defer it if the work in the fields is not finished.” But she also remarked in a letter of December 12, 1860, of her fears of a slave revolt if war were to break out.

In January 1861, the house journal, amid rumors of war, reports that the people enslaved there continued to protest their loyalty and declare their happiness at the convent. The same month, Louisiana seceded from the Union. The Union army quickly moved to capture the important port of New Orleans. By April 1862, New Orleans fell and by May, the ironclad Union gunboats had moved up river and were docked at the quay of St. Michael’s. The territory on the riverbanks was hostile, and the Union authorities were suspicious of the local planters and landowners, suspecting that they were harboring arms and combatants. Irish-born Mother Shannon, following the example of other planters of French ancestry, sought to protect the school by raising the French flag. She was directed to raise the Stars and Stripes, but refused, citing the sensibilities of her students’ parents (and perhaps her own).

The Union troops used the school as a place to interrogate local planters suspected of plots. Mother Shannon diplomatically invited the Union officers to tea, and when soldiers arrived to search the school for contraband, a feast was served to them under the trees. The presence of Union forces and the unrest among the local Black population led to the fear among the RSCJ that an uprising was imminent. Mother Shannon seems not to have trusted the local enslaved population to spare the school: on one particular night, she kept vigil with two other religious, intending to sound an alarm so all could go to the chapel to await death. Her fears may have been stoked by Fr. Claude Anthony Tholomier, the chaplain of the house, repeating commentary from the convent’s former gardener comparing the local community of enslaved workers to “Fenians,” an Irish revolutionary movement.

By September 1862, four enslaved persons – Stanislaus and his brother Martin, John Clem and one woman – had seized their own freedom and fled the property. The men joined the U.S. Colored Troops. The woman, whose name is unknown, died in New Orleans of smallpox. The U.S. Colored Troops saw action not far from St. Michael’s, capturing Donaldsonville. During the war, the convent and its inhabitants were close to the movements of the Union ships up and down the Mississippi as well as local fighting. Among the refugees arriving at St. Michael’s from Donaldsonville were eight Sisters of Charity, who came along with their 14 orphan charges and four enslaved women. Fighting and destruction also came close to the foundation in Natchitoches.

By 1863, the formerly enslaved persons could no longer be forced to stay on plantations in Union-occupied Louisiana. If they chose to stay, they were legally entitled to pay at a rate set by the Union general. There are, therefore, records of some wage payments made that year. However, it was evidently not enough. On January 1, 1864, the formerly enslaved workers of St. Michael’s presented a petition to Mother Shannon asking for higher wages. She refused, saying they were free to seek work elsewhere. By the end of 1864, however, it seems from the financial records that the wages decreed by the Union general were being paid to the workers at St. Michael’s. The financial register records the following wages for 17 servants as a result of General Banks’ orders: at $8 a month Washington, Joe, Dick, William, Eliza, Rachel, Davis, Betsy and Philomene; at $6 a month Clem, Jose, Esther, Mary Ann and Elizabeth; at $2 a month Roselle, Odilie and Celestine.

At the end of hostilities, the superior wrote the following in a letter:

We have sent away all the Negroes except two, an old man and his wife who have always been wise and good workers. The others were sad at the departure. Happily, these poor people have found good places with our neighbors near the church. I think it is better for the houses of Louisiana not to cultivate the fields, at least for a few years. Our Mother Foundress had a recommendation about this, but the present circumstances did not exist then” (Anna Shannon to Mother Josephine Goetz in Paris, January 20, 1866).

Following emancipation, census records show that some who had formerly been enslaved at St. Michael's found housing in the area but still worked at the convent. One reason many enslaved workers did not leave the RSCJ (or other former enslavers) is because they had nowhere else to stay and no one else to work for, and contraband camps were overcrowded. Some of those who stayed included the Spaulding family, the Clem family, and the Stewart family. Eliza Nesbit married at least twice but continued to live nearby and work at the convent, devoting herself to the special care of the sick through a private vow of charity renewed each year at Pentecost until her death in 1889. In December 1866, a list of the first names of those employed at St. Michael’s includes the following: Washington, two men named John, Joe, Clem, Alfred, Eliza, Philo, Rachel, Rosella, Louisa, Adelaide, Rosina, Odelia (/Odilie) and Celestina (/Celestine). Washington and John, referred to as the Bakers, remained there all their lives, as did Eliza Nesbit.

Following emancipation, census records show that some who had formerly been enslaved at St. Michael's found housing in the area but still worked at the convent. One reason many enslaved workers did not leave the RSCJ (or other former enslavers) is because they had nowhere else to stay and no one else to work for, and contraband camps were overcrowded. Some of those who stayed included the Spaulding family, the Clem family, and the Stewart family. Eliza Nesbit married at least twice but continued to live nearby and work at the convent, devoting herself to the special care of the sick through a private vow of charity renewed each year at Pentecost until her death in 1889. In December 1866, a list of the first names of those employed at St. Michael’s includes the following: Washington, two men named John, Joe, Clem, Alfred, Eliza, Philo, Rachel, Rosella, Louisa, Adelaide, Rosina, Odelia (/Odilie) and Celestina (/Celestine). Washington and John, referred to as the Bakers, remained there all their lives, as did Eliza Nesbit.

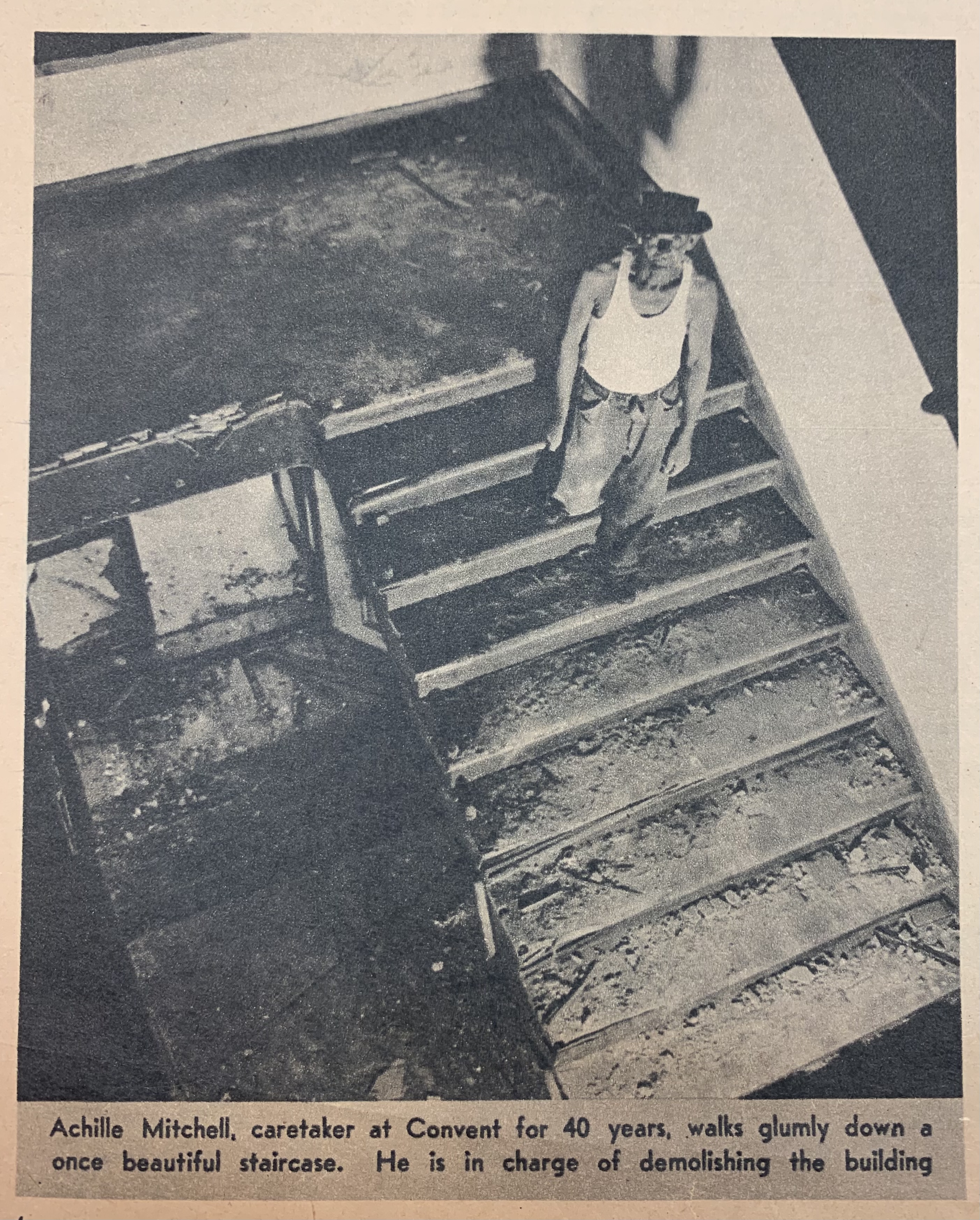

The boarding school remained open until 1927, then was occupied until 1931 by Mexican RSCJ and students in exile. The Black School, begun in 1866, continued on the property until 1932, then transferred to the parish under the direction of the Holy Ghost Sisters, closing in 1966. The main school buildings were torn down in 1947 when the property was sold (see photograph). Eliza Nesbit’s great-granddaughter, Georgina Trim, born in Convent in 1885 and married to Achille Michel (in photograph) in 1908, was still living near the property with her husband in 1967.

Researched and written by Emory Webre and Maureen Chicoine, RSCJ.

References

Archives, Society of the Sacred Heart United States - Canada Province (USCA)

General Archives, Society of the Sacred Heart, Rome (GASSH)

Letters of Mother Anna Shannon, Life of Mother Anna Shannon, anonymous, translated by Ellen McGloin, RSCJ

Callan, Louise, RSCJ, The Society of the Sacred Heart in North America. London, New York, Toronto: Longmans Green and Co., 1937.

Sacramental registry of St. Michael Church (SMI), St. James Civil Parish, Diocese of Baton Rouge, Louisiana