A note before reading

We offer reflection questions as an accompaniment to an individual or collective reading of this material. You are encouraged to use these questions to deepen your reading and prayer and to help direct your individual or collective reflection.

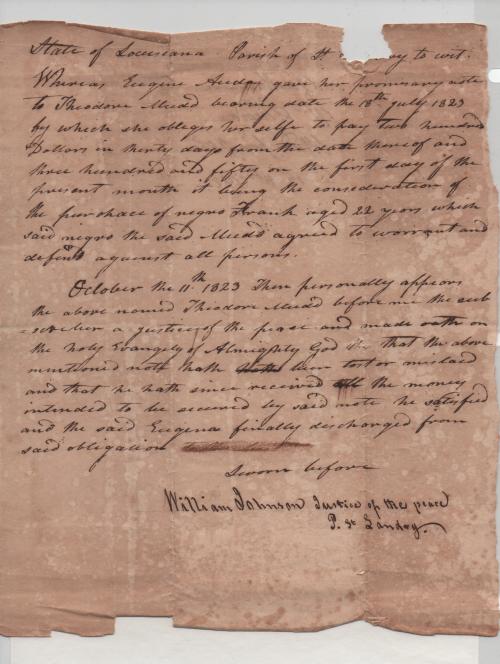

Mother Xavier Murphy, RSCJ, purchased* Jenny Eaglin Hawkins and her two children, Frank Jr. and Ben, in 1829. An entry in the house journal for December 8 refers to this event, describing Jenny and her children having “finally come to live here, full of gratitude to Mother Xavier, who brought them in order to alleviate their lot.” The person who documented Frank Hawkins' death on February 9, 1842 referred again in that record to the general feeling in the convent that Hawkins held a lifelong “respect mingled with veneration” for Mother Xavier, perhaps due to her role in reuniting his family in 1829. The couple had three other children, according to sacramental records: John Henry born in 1832, James in 1834, and Marie Anne Xavier born in 1840.

When he arrived in 1823, Frank Hawkins joined other enslaved persons on the convent property whose exact origins are unknown. Melite, an elderly woman, is mentioned in the house journal in 1829 when the Society purchased* her husband Martin, with no mention of how she had come to be there herself. Records do not indicate the presence of a slave cabin on the property in these early years, but there are mentions of several purchases for Frank Hawkins: a shirt, coat, blanket, tobacco and shoes. Other mentions of enslaved persons during this time in the house journal refer to them receiving sacraments or attending Mass at the Convent. In 1826 a woman named Philis and her two small children were purchased* but are not mentioned again in Convent or church records. A letter refers to a woman purchased* as a cook who was "sent away" about this time, who might be Phillis, though no mention is made of what was done with her children.

During the period from Frank Hawkins’ purchase* until 1834, there were a number of improvement projects underway at the Convent: a formal garden, fish pond, building a fence, planting trees, making bricks for an addition to the school and the construction of a large cabin for the three enslaved families who were by then living on the property. These improvement projects were undoubtedly made possible by the labor of enslaved workers, in addition to free persons who the records show were occasionally hired for specific tasks. Enslaved workers were also responsible for much of the day-to-day labor needed to keep everything running, such as laundry, cooking, cleaning and caring for the farm and any livestock. There probably was a wagon or carriage, drawn by horses, for local transportation, requiring care and a driver.

Frank Hawkins was entrusted with the task of going to Opelousas to make purchases for the school, and a purchase of tools indicated as being for Hawkins’ use indicates that he was likely a skilled worker in an area such as carpentry or masonry. The convent’s enslaved workers may also have been responsible for the production of bricks made by hand that were used for building outbuildings and additions, and which were donated to the Jesuits to start the building of their school in 1838.

Another family was reunited in 1833 when David (Dave) Eaglin, age 20, was united with his sister Jenny Eaglin Hawkins upon his purchase* for $600 from Joseph A. Gardiner by Mother Xavier after he came to the area with the Gardiner family, who moved from Maryland about 1832. He appears as a baptism sponsor, along with his wife Julia, for his nephew John Henry Hawkins’ baptism in April of that year. The day Eaglin arrived to live at the convent, he and Julia were married in church. Julia Eaglin, sometimes referred to as Julia Ann, made her First Communion at the Convent in 1836. The Eaglins appear often in records serving as baptism godparents or marriage witnesses. They worked and lived at the Convent until their deaths in the late 19th century.

In 1834 the Convent Journal notes: “we have erected a place to house our three families of Negroes.” That building, with newer additions, still stands behind the main house of the Convent of the Sacred Heart. The three families were probably Martin and Melite, who were then in their 60’s; Frank and Jenny Hawkins, with their 4 boys; and the newly married David and Julia Eaglin. There may have been other cabins added, especially in 1850-1860, when the enslaved population increased. The middle section, as the building stands today, which was positioned near a well (later covered by a swimming pool), was probably a laundry. The cabin beyond the laundry may have been erected at some later date. From 1840 to 1860 there must have been other small cabins on the property to house other enslaved families and individuals who were then living there.

The first RSCJ died in 1823 and 1830, and were buried in the church cemetery, but by the time of the death of Mother Xavier Murphy in 1836, the RSCJ were buried in the new convent cemetery, where others would be laid to rest in subsequent years, with their graves dug by Frank Hawkins, Dave Eaglin, and others who served as pallbearers. Enslaved persons were buried in the church cemetery: the first to die was Martin, in 1835. His wife Melite survived until she was over 100, dying in 1859.

Frank Hawkins and his sons provided the main labor force at the school for years. In 1840, a rumor of a slave uprising in the area caused him to be taken into custody for questioning, according to the house journal, which records the event in some detail: “A plot of the Negroes against the whites has caused at this time many court summons. Our poor Frank has been arrested; his family are plunged into grief.” The journal goes on to describe his wife going “sobbing to the feet of the Blessed Virgin,” while the rest of the enslaved community join in fervent prayers for his safe return. There is great relief when, later that same evening, “Frank, declared innocent, comes back to us. Their joy is great, and they all return to the chapel together to offer to God and to Mary their heartfelt gratitude.”

Another couple, Wilson Jacobs and Marie Louise Phillips, first appear in sacramental records as people enslaved by the Convent in the record of the baptism of their daughter Clara in 1849. Marie Louise Phillips died at age 39 in 1859, leaving ten-year-old Clara and her older brother Firmin, aged about 15. Wilson Jacobs does not appear in the burial register of the church or any census record, so his fate is unknown. Due to the presence of people formerly enslaved on the Hardey plantation as witnesses in later church records for Firmin and Clara, it is possible that Jacobs and Phillips were also previously enslaved by the Hardey family, who arrived in 1816 in Grand Coteau. An enslaved man named Wilson appears in Jesuit records in 1845-46 with a slaveholder named Alphonse de Bayon, clerk to sugar planter Francois Robin. From later records it is clear that all the family were born in Louisiana. This evidence points to the possibility that this is the same Wilson as the Wilson Jacobs recorded later as being enslaved at Grand Coteau.

The names of other couples appear as witnesses in the sacramental documents recording baptisms and marriages among those enslaved by the Convent, but their surnames are not given. These include Bill and Josephine, Veslain and Eugenie, August and Rosaline, Ignace and Eliza, Peter and Eliza, and August and Eugenie. Several of these couples also had children. Since, by law, children born to enslaved mothers automatically became enslaved persons themselves, the population of enslaved people on the Convent property grew over time. By 1860, two thirds of the persons enslaved on the Convent property had been born there, not purchased.*

Society tradition has held that the RSCJ, as educators, also taught the enslaved children on the property to read and write. However, the census records do not bear this out, as all of those enslaved at Grand Coteau as children appear in later records as illiterate adults. None were able to sign their marriage register with anything but an X. The RSCJ did teach both adults and children their prayers and basic catechism, but this was probably by rote memorization.

In 1865, after emancipation, a number of formerly enslaved persons still living at the Convent entered into an agreement with the Convent property overseer, Benjamin Smith, to remain there as paid employees, although it is not always known for how long. These people included Dave and Julia Eaglin, Jenny Eaglin Hawkins Martin (who had married Jesse Martin after Frank Hawkins’ death), Jenny’s son James Hawkins and his wife Emeline and their two or three children, and Jenny’s other son Ben Hawkins and his wife Caroline and their six children. Firmin Jacobs, then 20 years old, and Clara Jacobs, aged 16, also remained. Kitty, perhaps the wife of Henry Eaglin, along with Rosalie and her family – whose last names are unknown – also appear on the list of employees in 1865.

After emancipation, census and other records continue to provide significant pieces of information about the now freed men and women associated with the Convent of the Sacred Heart. Dave and Julia Eaglin lived and worked there until their deaths. Dave passed away in 1881 and Julia, or “Aunt Julia,” as the religious referred to her in their Convent records, passed in 1891. They were mistakenly identified in the 1870 census under the name of “Hawkins” and listed along with four Hawkins children aged 9 to 19. These children do not appear in any local church record, and their parents are unknown. Jenny and Frank Hawkins’ son James died around 1879 when he was just 45, but the 1880 census records that his wife Emeline and their children were still living on the Convent property a year later.

Both the 1870 and 1880 censuses record the names of Jenny Eaglin Hawkins and her second husband Jesse Martin. Jenny had reached the age of 105 when she passed away in 1890. Jesse’s place and date of death are not known. Frank and Jenny Hawkins’ son Ben and his wife Caroline appear in the 1870 census as “Hawkings.” Caroline died in 1871, and two years later Ben married the widow Mary Clark. The couple had several children and the names of their entire blended family are noted in the 1880 census. Almost everyone in the original Hawkins family, along with their spouses and some of their children, were buried by 1880; descendants moved to Lake Charles, Louisiana, before moving on to Beaumont, Texas.

Firmin Jacobs married Mary Linton in 1865 and the couple had 5 children. After Mary’s death, Firmin married Marie Lavergne in 1878 and the couple had 11 children. The family name appears in census records up through 1910. Firmin’s occupation is listed as butcher. He was around 60 years old when he died in 1916 and was buried in the St. Landry parish cemetery in Opelousas. In 1866, his younger sister Clara married Ozee Eaglin (sometimes also called Hosea or Ose). He had formerly been enslaved to R. Hardey. When Ozee died at age 36, having had 11 children with Clara, she married Alphonse Senegal, with whom she had at least 3 more children. Clara, Ozee, and Alphonse are all buried in the St. Charles Borromeo parish cemetery. The name appears in census records up through 1910.

In 1875, the RSCJ in Grand Coteau opened a school on the Academy grounds to educate young African American girls. The religious taught 16 girls in the living quarters of the people formerly enslaved by the RSCJ. By 1888, the school included boys and needed more space. With contributions from the archdiocese, the international Society, and the Jesuits of St. Charles College, a new building was erected on the convent grounds. The name of the school, Colored School of the Sacred Heart, was changed to St. Peter Claver School in the 1930s, and the school was relocated nearer St. Peter Claver Church in Grand Coteau in 1939. In 1947, the RSCJ withdrew from the administration of the school in favor of the Sisters of the Holy Family, but RSCJ continued to teach there for some years.

As of this writing, a number of living descendants of Jenny and Frank Hawkins have been located. They are descended through Jenny’s and Frank’s sons, James and Ben, and their children and grandchildren. Living descendants of Wilson Jacobs and Marie Louise Philips have also been located, descended through their children, Firmin and Clara, and their children and grandchildren. So far as is known today, it appears that David and Julia Eaglin did not have children. Living descendants of two other couples, Frank Hawkins Jr. and Marguerite, and John Hawkins and Rose Eaglin, have not been located.

Researched and written by Maureen Chicoine, RSCJ.

References

Callan, Louise, RSCJ, The Society of the Sacred Heart in North America. London, New York, Toronto: Longmans Green and Co., 1937.

House journal and financial records, 1821-1890, USCA

Work agreement of seven formerly enslaved families 1865, USCA

Legal documents and property records, Grand Coteau, USCA

Census records, St. Landry Parish, 1820-1890

Sacramental records, St. Charles Borromeo Church, Grand Coteau, LA