To shed and surrender

The good Lord somehow has a great sense of humor when it comes to walking with me in my life. He has a way of following you, haunting you, making you move even when you are unsure of your path, not knowing where you are to go or how you will ever get there. It seems that is how I have experienced this; others have too.

As I traveled to McAllen, Texas, from Chicago, Illinois, ready to learn, to listen, to be with those who are living their daily lives in a state of chaos, there at the border, the frontera, I knew I had to be silent to take it all in.

I knew that I had to leave behind preconceptions, voices, opinions, my professional training, my judgments, my home, my comfort and my family. I had to shed the trappings of my daily life: my list-making and goal-setting, and worrying about the things in my family’s lives that are ultimately, and in reality, out of my control.

I had to leave behind my community of church, schools, friendships and marriage, and my sense of belonging and ownership within my daily life. These were the very small risks taken by me. I was very conscious entering the experience that this was temporary for me.

I surrendered to the experience of the Border Witness Program, hosted by the Society’s Stuart Center in partnership with ARISE (A Resource in Serving Equality), a nonprofit working to organize local Texas residents in leadership; personal, child and youth development; education; environmental awareness; and immigrant support. ARISE has a standing relationship with the Society of the Sacred Heart, United States – Canada Province, and hosts Border Witnesses programs like the one I experienced. For four days I joined a new community of Sisters and Associates, submitting to the schedule of events arranged by our leaders, Reyna Gonzalez, RSCJ, and Imma DeStefanis, RSCJ, and our local hosts Ramona Casas and Eva Soto, staff and leaders at ARISE.

Three days of witness

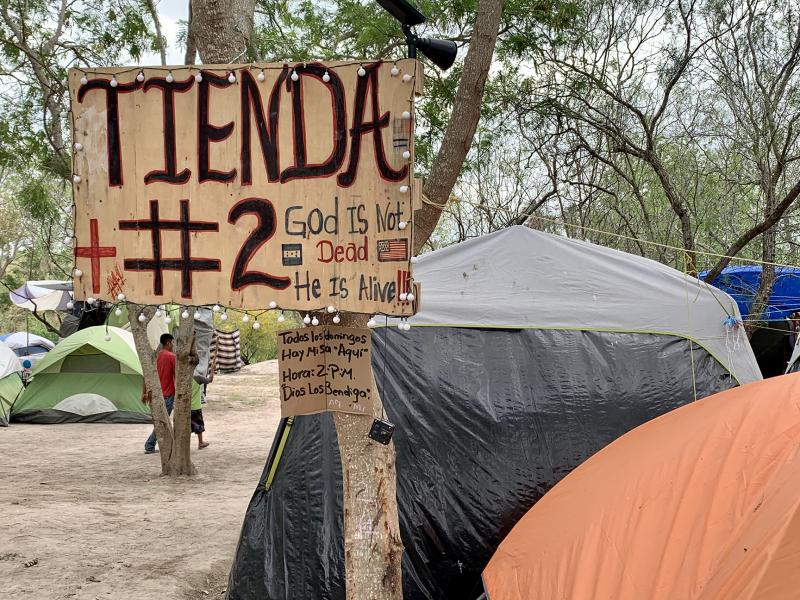

We experienced a mile-long walk along the United States – Mexico border wall, overlooking a “no-man's” land between Reynosa, Mexico, and Hildago, Texas. The next day we witnessed the reality of the tent city at Matamoros, Mexico, just steps from the crossing at Brownsville, Texas. This tent city at Matamoros houses some 2,500 immigrants from all over South and Central America, and beyond, and was created in response to the U.S. government policy known as MPP (Migrant Protection Protocols), which require asylum-seeking refugees to wait in Mexico for their U.S. court cases to resolve. Months and months later, families are still awaiting court dates, as the timetables seem to unwind, with massive case loads created by the forced migration of so many refugees fleeing gangs and drug cartels, violence in their homelands that are crippling their national governments, and local police forces.

Another day, we had the opportunity to visit a sparsely-populated but eerily well-ordered converted nursing home being used as a detention center for 12-17 year old girls while they await the resolution of their asylum cases and/or reunification with identified family members in the U.S. No interaction with the residents was allowed, but we stole glances and some smiles when we could with the rigidly-seated school girls, as they read Harry Potter in Spanish.

The facility remains fully-staffed while the population of residents has diminished to near empty, because of MPP. I couldn’t help but think there were so many guards for so few young girls! We asked many questions of the staff and leadership there, and they seemed well-disciplined in answering in the institutionally-acceptable manner. The next day, we woke to read a newly-published New York Times article documenting that confidential statements made in counseling sessions at that very facility were used against a former resident in repeated court hearings to deny asylum to the child. This reality was hardly what the standard of care would be or what we would expect for our own children in the courts, regarding clearly-represented privileged conversations.

We benefited from interacting with, listening and questioning many experts and activists with vast knowledge and experience on the border, who daily grapple with the issues. We heard from several women leaders from ARISE, several of whom spoke to us of their personal journeys crossing the border in varied circumstances – their stories amazing and moving. You could not hear them without acknowledging the courage each woman had as they endured severe circumstances, unknown odds of survival, risk of imprisonment, and fears of discovery, deportation and return, which would mean separation from family and communities they had carefully and painstakingly created around themselves and for their families. Several of these strong women, who now share enviable community and faith lives together, spent years cowering behind closed doors. They are now powerful voices for their communities, examples for their children, and guides to help us navigate these issues, without the fear that they had to endure, and with the courage that they found to come out of hiding and find pathways to citizenship and full participation, sharing their tremendous gifts with a country that needs them.

We heard from Ligia Mencia of Honduras’ Save The Children. She shared about the current conditions in Honduras that are driving the patterns of forced migration we hear about in the news. She reinforced the message that was clear from visiting Matamoros and other sites: that no one chooses to leave their homeland and the safety of country, home and family, unless those places, structures and institutions are not safe, are threatened and, under current conditions, are in fact, threatening lethal jeopardy to Honduran citizens and citizens of other similarly-situated nations across the Americas.

My own opinion became this: one reason we see so many pregnant women, young mothers, fathers and tiny babies traveling and enduring the many life-threatening risks they encounter on the road to make this crossing is because the risks of staying are so much greater. What these individuals may endure in a dangerous environment becomes impossible to contemplate subjecting your new, innocent children to. Their goal is not “the good life” or “easy street” in America, but this: life, that is, survival, freedom from danger, the safety of one’s children, an ability to make a simple life where risk of mortal harm is not around every corner.

We also had the great gift of meeting Sister Norma Pimentel, MJ, the executive director of Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley. She is a true force of nature, a woman with single clarity of mind and purpose. She has and is guiding the delivery and organization of services to the people of Matamoros, working with all concerned service agencies and donating charities to reduce duplication of efforts. She has worked with donors and with the city of Brownsville, Texas, to create a Humanitarian Respite Center. We visited the center in downtown Brownsville, directly across from the bus station, a hub for all the major bus companies serving cities across the U.S. She is in the business of “restoring human dignity,” to memorably quote her.

Relationship and reflection

I found little clarity in the moments during this Border Witness Program, only more questions brought on by meeting mothers, fathers and children, parents holding newborns in their arms, all seeking the safety and security of their families. All were seeking safety for their children. It is universal, a human right, and impossible to deny our obligation to offer them aid. With companions in Matamoros, we met one man who had previously emigrated successfully with three older teen sons who were waiting for his return to New Jersey. He had courageously returned to Honduras to rescue his three youngest sons and his wife from the gangs and drug cartels who threatened to recruit or, alternatively, harm his young boys, all less than eight years-old, who played soccer next to us in a small unevenly-pitted dirt crossroads. Their soccer shoes were flip flops. Their ball was a small, deflated beach ball. This was also the same space the community had gathered just one day before for Sunday Mass. This father of so many sons was busy stringing rope across several trees to support a tarp that they were using to create a space for school, La Escuela, in the center of Matamoros’ tent city.

In the smaller, crowded escuela nearby, we met a young mother holding her beautiful, engaging 5-month-old daughter. The baby smiled and charmed us while we learned from the young mother that she had journeyed pregnant to the border, leaving behind her young son with her own mother in Honduras because she felt he was too young to make the difficult journey. She had given birth on the journey and was awaiting a future court date still months away. She was helping in the school because she found community among the mothers there and because she could be close to children her son’s age, a voluntarism that I can only imagine may have both comforted and tormented her.

In the respite center, we met another set of young mothers, one who napped her 21-day-old newborn baby while she helped to sweep up the floor and chase after her active and energetic 4-year-old daughter. Another mother-to-be there was two weeks from her due date and was desperately trying to reach her husband in Oklahoma, who was there preparing for her and the arrival of their first child. She had made the journey in the late term of her pregnancy, travelling on foot from Honduras, as well.

I cannot claim that I came away with Sister Norma’s clarity of purpose or definitive answers. I am still struggling to know what I am to do with all that I learned and saw and heard. I know that it has deeply changed me and I am still discerning my personal response. This requires steps without knowing all of the answers or even knowing that I am right or wrong. This is hard for me, but very necessary, because it is this new attitude that will allow me to move from a place of unknowing, to grow into a place of compassion. I hope to develop some of the skills necessary to address the clear problems and wrongs that occurr in systems that need our healing action: for the good of the people – mothers, fathers, sons and daughters, teens and babies – that are caught up in our failure to meet them well and provide for their needs, in their time of greatest, most severe and urgent necessity.

The road. The river. The wall.

Shortly before this Lenten Season, I returned home to my own comfortable place, my crazy home filled with a lot of noise, bustle, kids, meals, laundry, study and sports. The city of Chicago, which is a city on the move, is one home to many people who struggle to remain hidden from those who would return them to danger and violence. In many ways, we all live on the border when we live in a country so large, modern and accessible. Let us never forget.

I plopped down on my sofa, facing my fireplace surrounded by three paintings I have loved and collected over many years. One on the left, an open sunlit straight road between lines of birch trees. One above the fireplace, a wide beautiful river scene, with overhanging green trees at dusk. One on the right, a field of sheep in the distance on a dappled sun-lit hillside, surrounded by a loose-draped fence of gentle wire enclosing them.

The road. The river. The wall.