Written by Mary Frohlich, RSCJ

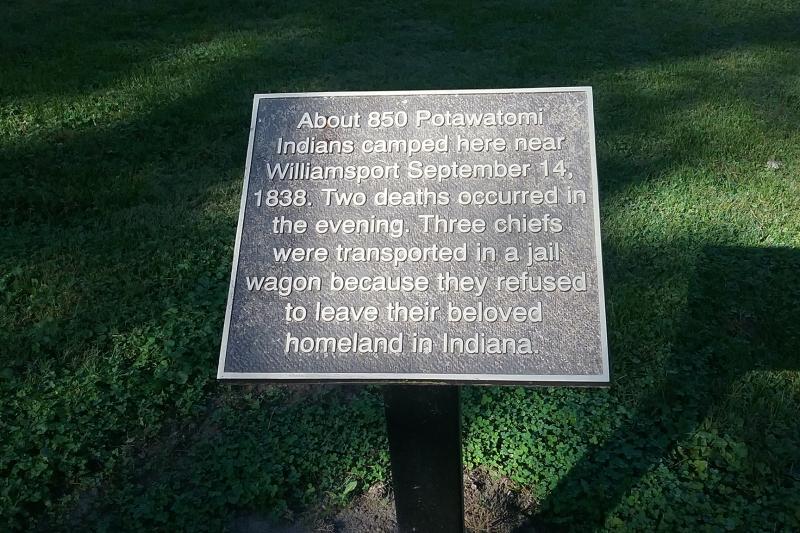

On September 4, 1838, 859 members of the Potawatomi Nation began a forced relocation march from their home near Twin Lakes, Indiana, to lands to be given them in Kansas. Their chief, Menominee, refused to sign the removal papers and so he was transported in a prison wagon. Water was scarce due to a drought, and typhoid was ravaging the land. By the time they arrived in Osawatomie, Kansas, 61 days later, 41 Potawatomi – mostly children – had died and been buried along the trail.

Three years later, on June 29, 1841, four Religious of the Sacred Heart (RSCJ) departed from St. Louis to found a school for native girls at the Jesuit mission in Sugar Creek, Kansas, where the Potawatomi had ultimately settled. Among them was Rose Philippine Duchesne, age 71. Since she had been a young religious in France, she had fervently desired to minister among the Native Americans.

Sadly, Philippine’s health permitted her to remain at the Sugar Creek mission for only one year. The Potawatomi, however, never forgot her. To this day, they pass down memories of Philippine as “she who prays always.” On July 3, 1988, Rose Philippine Duchesne was canonized.

The 2018 Trail of Death Caravan

Every five years since 1983, the Potawatomi have organized a caravan to retrace the Trail of Death. They stop at many of the places of encampment to do ceremonies and to remember the dead. Since 2018 is the bicentennial of Saint Rose Philippine’s arrival in the United States in 1818, the Religious of the Sacred Heart asked to join the Potawatomi on their caravan as part of our own remembering of Saint Philippine and our mission to the native peoples.

The 2018 Trail of Death Caravan took place from September 16-22. Only one RSCJ, Deanna Rose von Bargen, and one RSCJ Associate, Mary Jane Tiernan, were able to complete the whole journey. With them also was Sister Mary Seibert, MSC. Four other RSCJ, plus two teachers from Network of Sacred Heart schools, took part in portions of the caravan. I was able to participate in its first four days.

The days started early with breakfast and a preview of the day’s stops. By 8 a.m. all the cars, vans and trucks (as many as 17!) were lined up in the parking lot and ready to go. Each vehicle bore a blue “Citizen Potawatomi Nation” flag that marked it as a member of the Trail of Death caravan.

It was quite an adventure to try to stay together while navigating both city streets and “middle of nowhere” back roads! In fact, we did get separated sometimes and even GPS had trouble figuring out where we were on some of those obscure back roads.

Most of those who saw us coming probably presumed we were a funeral procession, since the flags flapped too hard to be easily read. In the rural areas of Indiana and Illinois, I was impressed with how consistently people pulled over to the side of the road for us, showing great respect. One elderly man, in faded blue overalls and carrying a hoe, stood at attention by the side of the road with his hand over his heart as the long line of cars passed by.

During the 35 years since they began retracing the route of the Trail of Death, the Potawatomi have advocated for, and coordinated the placement of, dozens of historical markers at points were the original exiles passed by or camped. While the caravan could not stop at every one, we would at least drive by and slow down with respect.

In between times, there was a good deal of banter – as well as information – traded back and forth on the citizen’s band radios that helped us stay in touch with each other.

About seven or eight times a day, the caravan would stop at one of the markers and everyone would get out. Often one of the Potawatomi would give some historical background about that site.

Shirley Willard, age 82, has devoted much of the last few decades to studying the history of the Trail of Death, as well as organizing these caravans. She swears this will be her last one – although it was pointed out that she said that last time, too! George Godfrey is another tribal leader who has done a great deal of work on the history and has helped with organizing the trips. Finally, Robert Pearl, age 92, and his daughter Janet could often add interesting details.

For lunch, we usually stopped at a restaurant or truck stop, but most of our suppers were provided by local groups who were eager to support the native peoples.

On Wednesday evening, for example, the people of Quincy, Illinois, provided an abundant potluck supper on an island in Quinnipiac River Park. The meal was preceded by a ceremonial rededication of the historical marker by native leaders using chanting, gestures and a circle walk while sprinkling tobacco. In addition, the mayor of Quincy offered a commemorative proclamation of the city’s support for the native people.

Often we commented on how different our experience of riding in air-conditioned cars and staying in comfortable motels was from the experience of those who actually had to make the original forced march of the Trail of Death. We felt exhausted, yet how much more so the people who were losing everything they had known.

Commentaries from 1838 note how dejected the people were. They had no idea what awaited them at the end of the journey. Almost every day, one or more children died, adding to their despair.

The Potawatomi who made the 2018 Trail of Death expressed how emotionally demanding this journey is for them, each time they do it. Even 180 years later, they deeply feel the injustice and sorrow of what happened to their ancestors.

As Religious of the Sacred Heart, we, too, entered into this sorrow. Our ancestors were not on the Trail of Death, but they became companions and educators for the Potawatomi as the native people strove to re-establish themselves in their new circumstances. We are glad we can continue that companionship today, and now it is the Potawatomi who are educating us.