The following material is an essay from the book Southward Ho! The Society of the Sacred Heart Enters “Lands of the Spanish Sea.”

By Sharon Karam, RSCJ

It may be hard for a reader with geographical savvy to swallow the thesis that Grand Coteau, Louisiana, was once an international crossroads vitally connected to Canada, Europe, Latin America, and New Zealand. From the perspective of this writer, aided by the instantaneous nature of e-mail and the Internet, international access and communication are easily possible, but surely in the frontier days of the nineteenth century, this could hardly have been the case. Yet journals of the house, and especially a journal kept in the trilingual novitiate of the convent in Grand Coteau from 1873 to 1896, indicate a vibrant correspondence with other countries and a truly international perspective in a time when communication was unreliable and its pace as slow as the bayou behind the convent property. Currently the oldest house in continuous history in the Society of the Sacred Heart, Grand Coteau is well known as a school and former college, but its internal history as an international novitiate and a site from which RSCJ were commissioned to open new houses in other countries is less well known. This essay attempts to provide an overview of that history, and particularly of the five remarkable women who served as either superior or mistress of novices (and usually both!), to interest its readers in learning more about this most unusual site in Acadiana, and perhaps to spur future researchers to dig deeper into the cross currents of international communication in the Society.

From the opening of the house in 182I, novices were accepted and were trained at Grand Coteau until 1825 when several novices helped make the foundation at St. Michael's in St. James Parish[i] -the town became known as Convent in 1869. Novices were trained at St. Michael's until 1848 when Mother Maria Cutts brought the novitiate back to Grand Coteau.[ii]

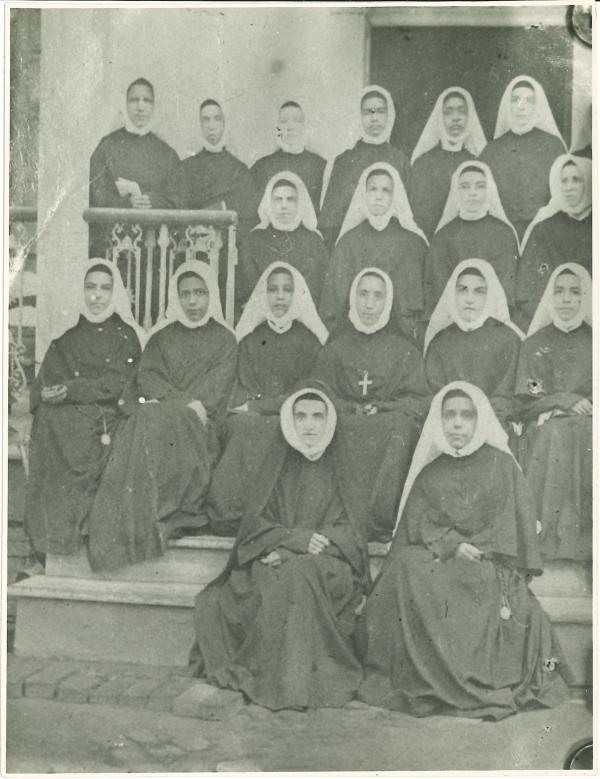

In 1874 the house of Havana, formerly part of the vicariate of New York, was attached to the vice-vicariate of Louisiana, and Spanish speaking novices from Cuba were sent to the novitiate in Grand Coteau. Later, both Puerto Rican (1880-1896) and Mexican (1883-1896) novices joined English- and French-speaking novices in the Grand Coteau novitiate. This arrangement continued until 1888 when Grand Coteau became a house of the Mexican Vicariate and the novitiate kept only the Spanishspeaking novices; with a few rare exceptions, the others (English- and French-speaking) were sent to St. Michael's. The novitiate continued at Grand Coteau until it was determined in 1896 to move all Spanish-speaking novices to Europe and all-American novices in the south to Maryville in St. Louis.[iii]

What is remarkable about this period, and indeed the very nature of this trilingual novitiate, is the keen sense of internationality in a very rural place, and the vibrant sense of being trained to take the mission of the Society to new places. Consistently the novitiate journal refers to communication between the novices at Grand Coteau and the other novitiates throughout the world. Also remarkable were the five religious who were responsible for their training during this period.

Victoria Martinez, RSCJ

Victoria Pizarro Martinez was born in New Orleans in 1815 to Francisco Pizarro Martinez and Maria Teresa Visoro. Mr. Martinez, Spanish by birth, was the Spanish consul in Mexico and then, after Mexican independence, Mexican consul in New Orleans. From a very early age, Victoria exhibited unusual spiritual gifts and a desire to teach others the faith; as a child at the Ursuline Academy, she was observed taking great joy in teaching the catechism to the poor and the domestic help. At a very young age, she reported to her uncle that she'd had a terrifying dream of a friend dying in a burning house; the uncle dismissed this as perhaps a mild illness on Victoria's part, until the next day, when it was discovered that the friend had indeed died in a fire. She followed her sister to the Sacred Heart Convent in St. Michael's, Louisiana, and apparently the school became a major factor in her spiritual formation and her desire to become a Religious of the Sacred Heart. Before going to St. Michael's, she had experienced a serious stomach ailment; after five weeks away at school, she had no recurrence of the ailment, but upon returning home, it reappeared. Back at school, it disappeared again. She clearly credited her mental and physical health to the spirit of the school.

Several years later, she asked her father's permission to enter, and though he formally opposed the move, he did finally consent to her entrance, though with a somewhat embittered attitude, even calling her an ungrateful child as she left home definitively. Strong of will and character, Victoria appeared undaunted by this rebuff, yet the record notes that she found it very difficult to leave her five-year-old sister Teresa. Fifty years later, in a letter to her sister, Victoria notes that the first Sunday of November 1833 when she received permission to enter, was the "feast of my heart."

Her days as a postulant at St. Michael's were happy but very difficult. The house was poor and cold; there were no fireplaces; at one point she almost told the mistress of novices that she couldn't continue her work, but then realized someone else would have to do it. She continued her sweeping, her hands covered with blood. She loved the Office, and even prayed it on her own when she missed it. The community begged that she be allowed to receive the habit early, before moving to Grand Coteau; normally, this stage was preceded by a retreat. Given the circumstances, the superior, Eugenie Aude, sent Victoria to the chapel with the Imitation of Christ for half an hour; evidently, to her credit, this was considered a sufficient retreat for her. To Victoria's worry that she might be dismissed for delicate health, Aude responded, ''The only door I'll open for you is that of my room when you need me.” Victoria continued her religious life at St. Michael's, and made her final profession there. During her years there Aloysia Hardey was mistress general of the school and then superior, and Susannah Boudreau entered the noviceship.

In 1854, she was sent to Grand Coteau to assist Mother Louisa Leveque with the students. Within a year she was made assistant to the superior, Amélie Jouve, and had responsibilities in the school, with the adult sodality, plus assorted jobs such as sacristan. Former students and other religious note in their memoirs her candor, simplicity, kindness, and calm. By 1855, she was named mistress of novices as well. In this role, she was noted for being solicitous towards the newcomers, discreet, demanding but gentle at the same time. She taught the novices to meditate on the Psalms and had a gift for matching responsibilities to the capacity of each novice. Her teaching in many areas was remembered for its breadth of spirit, and she was known for preaching contrition for life, not for little things. The house journal notes that in August 1879, during a retreat given in English, Martinez repeated the points of meditation in French for the novices who did not understand English. Former novices noted that she was tender especially towards those who were ill or in trouble, but spared little for the smug and complacent. She treated the novices as sacred vessels, and expected them to become strong women. Some felt she could truly read souls, which is not a surprising reflection given her youthful experience of premonition of fire.

In 1864, when Amélie Jouve was called to France for a General Chapter, Martinez was made superior per interim; however Jouve did not return from France and the interim lasted ten years, which meant that she now combined the roles of superior, mistress of novices, and sacristan. She felt the burden of the new employment keenly. Never having traveled to France herself, she kept the community aware of the international dimension of the order by reading excerpts from letters from France which arrived quite regularly from Jouve. These provided news of the houses in France, of people Jouve and Martinez knew in common, and of the process of inquiry into beatifying Madeleine Sophie Barat.

It was her initiative which turned the novitiate room and Mary Wilson's bedroom into a shrine to John Berchmans, the young Jesuit who was credited with the miracle which cured Mary Wilson, a novice. Martinez had been present at the miracle, felt keenly the death of Mary Wilson a year later, and suffered much at the hands of some who mocked the nature of the miracle. Apparently her strength of character was both tested and proved in dealing with the reactions to this miracle, because one gentleman is reported to have responded to another who said he didn't believe in the Wilson miracle: "Well, I do, now that I've met Mother Martinez. Such a woman can never tell anything but the truth.”

When Mary Elizabeth Moran was named superior of Grand Coteau in 1874, Victoria Martinez quietly took her place as Moran's assistant, continuing also as mistress of novices. In 1881, after twenty-seven years at Grand Coteau, Victoria Martinez was called to New Orleans to serve as assistant to the superior, who happened to be one of her former novices. She was considered remarkable in her humility in putting herself at the service of someone she had trained, and strong in her spirit of service. Unfortunately, her health began to deteriorate, and she could do less and less. Realizing her failing health, Mary Elizabeth Moran invited her back to Grand Coteau in 1883. She was overjoyed and joined a community which included her own niece (she even asked permission to visit with her niece from the local superior, who was also one of her former novices). Despite her broken health, she insisted on teaching as she could, and had a small class in New Testament, making pictures for the youngest children. She died in December 1884, at the age of 69, during a Mass which was being said for her.

Stanislas Tommasini, RSCJ

A legendary figure, Stanislas Tommasini, replaced Victoria Martinez as mis tress of novices in 1881, and though she stayed in that role only two years, she left an indelible mark on the house and on the novices in her charge.

The novitiate journal for August-September 1881 records an unusually detailed and affectionate account of the news of Mother Martinez's move to New Orleans. Of particular note is the delicacy and thoughtfulness displayed by Tommasini upon arriving and realizing what this move meant to Martinez, who had been at Grand Coteau for 27 years, and for the novices who obviously held her in such high regard.

In anything written of this irrepressible Italian who loved life, music, people, and surprises, the key word is joyful. It is striking that in the journal of the novitiate, the novice-recorder includes much more detail of Mother Tommasini's conferences than in previous accounts, suggesting, among other aspects, the wide range of Tommasini's devotions, interests, and pedagogies. An example of her influence is illustrated in the note of October 15, 1881, just a few days after her arrival:

Our Mother [Tommasini] has a very deep devotion to St. Theresa, and gave us this afternoon, a little ceremony in her honor. We recited the Litanies of St. Theresa, and she related several interesting characteristics of Theresa.

Indeed, her two years as novice mistress appear to have been marked with a sense of openness, joy, wide community-building among professed, probanists, novices, boarders, and the Jesuits, who were even invited to community celebrations and entertainment. It is striking to note in the novitiate journal of December 28, just a few months later, that the Canadian novices, whom she had just left, wrote the Grand Coteau novices: "Our sister novices at the Sault [Montreal] wrote us two letters (one in English, one in French). Our Mother Tommasini, in coming here, has united our novitiate with theirs in an inseparable way. How true it is that the sacrifices which cause some separations only strengthen this dear Society." Just several days earlier, the novices had organized a presentation which divided the novices into groups, named for the houses of the Canadian vicariate which Tommasini had just left; the journal notes that this experience deeply touched Tommasini, who realized that her present novices knew what a great sacrifice she herself had made.

Tommasini's clear commitment to keeping these international connections is not due simply to her own movement across countries in her early religious life, but apparently to a desire on Sophie Barat's part to use Tommasini's natural gifts to bridge cultures. In communications with Aloysia Hardey at Manhattanville, where Tommasini was sent after the religious were expelled from the areas in northern Italy, Mother Barat instructed Hardey to have Tommasini study Spanish rather than French in order to be a link with the Latinas who were coming to study at Manhattanville, and the families who were apparently already requesting the Society's presence in Mexico. Thus, she was being prepared to be a link for new foundations, as well as a welcoming presence for Latin families who sent their children to schools in the United States.

While Tommasini was at Grand Coteau, she was several times summoned to New Orleans to confer with superiors, and presumably to help with plans for extending the Society into other countries. The journal records, in the same tone as it records who came for Mass and what treats Tommasini provided them during retreat (a jar of syrup!), the amazing expansion which was then going on as Grand Coteau welcomed novices from Cuba and Puerto Rico and the first vocation from Selma, Alabama, brought by Emma Chaudet. Details of Tommasini's short stay at Coteau abound with a vibrant sense of fun, of life, of teaching about the spiritual value of the present moment, and as always, of surprises: awakening novices at 4 a.m. so that they wouldn't miss the magnificent comet; relating stories of life in Rome; calling conges at a rate probably unknown before and after her tenure; allowing the novices unusual access to events in the boarding school, to the point that one entry in the journal jokingly notes that the novices were becoming worldly, going to entertainments almost nightly in the boarding school.

In spring 1883 she was asked by Mary Elizabeth Moran, vice-vicar of Louisiana and Cuba, to accompany her on an exploratory trip to Mexico to see if the Society should make a foundation in that country. As it turned out, she did not return to Grand Coteau for many years. In the fall of 1899 she was there for several months of rest after the thirty years during which she held positions of authority, including years as superior in eight houses in four countries. She returned to the East in 1900 and died at Kenwood in September 1913.

Justine Metzler, RSCJ

About Justine Metzler, mistress of novices from 1883 to 1886, less is known, but her generosity and flexibility were legendary, and the novitiate journal continually refers to her. Born in Nova Scotia in May 1831, she was the ninth of twelve children and among the first students at Halifax, where her mother moved the family after her father's early death. The move was sufficiently traumatic for Justine so that she became gravely ill and her mother moved back to the country until she recovered. Highly gifted in music and languages, she was also known as lively, intelligent, and affectionate. She made her own novitiate at Manhattanville, where she was received by Aloysia Hardey. After making her aspirantship in Halifax, she returned to Manhattanville for her profession in December 1862. Her generosity and flexibility matched the breadth of her assignments: from the Canada of her birth, to Manhattanville in New York, to Halifax, Havana, Grand Coteau, Mexico, and Puerto Rico.

Immediately before her assignment to Grand Coteau, she lived in Havana, as assistant to the superior and admonitrix. The emphasis during her time as mistress of novices was on her spiritual guidance of novices, adapting the novitiate exercises to fit each temperament, at one point impressing the novices by making individual meditation books. Devoted to the Mother of God, she was also marked by devotion to the Passion and recommended to the novices that they live at the foot of the Cross. Notes on her life indicate a strong belief, by those who knew her, that she had unusual skill in reading souls, –in today's parlance, discerning the heart. During these years, it is clear from the novitiate journal that spiritual exercises were given in French, English, and Spanish, sometimes alternately, sometimes in translation. However, since the majority of novices were now Spanish speakers, the novitiate journal records the observation that the Americans were proud that all but two could now understand exercise, which was given in Spanish, and that sometimes at recreation Metzler would create amusement by having the Americans and the Latina novices speak French. The journal also makes it clear that the novices regularly had letters from their sisters in Mexico, especially from Tommasini who expected to return to Grand Coteau but was made superior of the Mexico City house, and also from their counterparts in the French novitiate at Conflans. One such entry reads: “During retreat, Mother Metzler gave us for meditation the conference of Mother Lehon to the novices at Conflans for the feast of Saint Stanislaus ...“

After leaving Grand Coteau, Metzler served for two years as superior of San Luis Potosi in Mexico, then for two years as both assistant and mistress general in Havana, followed by two years as superior in Puerto Rico and another at Guanajuato, Mexico. She then returned to Havana before going again to Puerto Rico, where she continued her multiple employments until she became ill. Her last twelve days of life were spent in agonizing pain, yet those around her noted her peaceful and generous attitude, asking that the paragraph in the Rule about the final moment be read to her; just before she died on May 26, 1901, she exclaimed joyously, "Goodbye; to heaven.”

Emma Chaudet, RSCJ

Emma Marie Louise Chaudet was born in St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, June 30, 1844. She entered the Academy in Grand Coteau at age ten, with one of her sisters, and recorded that, "... on the great day of May 8, 1856, I made the determination to give myself completely to Jesus, as did one of my companions, later a sister in the novitiate...” Shortly after this experience her parents moved to New Orleans, and following a negative experience of schooling there, her father hired a tutor. Chaudet notes that after several years, she grew lax in her religious practice, yet knew that in her present circumstances Gad still pursued her, since into her hands "fell" a brochure entitled “The True Child of Mary.” Reading through the booklet re-awakened her desire to consecrate herself to God, and in 1863 she wrote to Anna Shannon, superior at St. Michael's, asking to enter; she was at this point nineteen. Shannon replied positively, and told her to come as soon as possible as travel was growing ever more difficult, with the federal troops controlling the roads out of New Orleans and the Confederates controlling the countryside. Despite these conditions, she arrived safely at St. Michael's and was accepted as a postulant.

After three months of postulantship, she left for Grand Coteau in the company of several Jesuits, and the trip, which normally took four hours on the river, took four days, as the group had to leave the river and take bayous and side roads, facing numerous challenging situations. Chaudet was received by Amelie Jouve, made her novitiate under Victoria Martinez, and began her apostolic life at Grand Coteau after making her first vows in December 1865. Later, she returned to St. Michael's, then on to Nachitoches in northern Louisiana, where she made her final profession and held multiple positions in the school. One of her contemporaries wrote the following account of her flexibility and obvious giftedness: the writer taught a higher level English class but lost her voice completely after an attack of bronchitis. Since the community was small, the only person free at that period was Emma Chaudet, who did not speak English (classes apparently were held both in French and in English). The superior told her she simply must take on the class, which she did, and kept the class for the rest of the year. She requested help with the corrections, so that she could see where her English needed improvement; the writer notes that not only did the students do "brilliantly" on their exams, but that at the end of the year, Chaudet was perfectly fluent in English. ln a similar vein, the same source notes that on one occasion when an organist was needed for a ceremony, Chaudet came forward, since she had some musical training, a good voice, and could even play the guitar a bit, and played with great success.

Chaudet was chosen as one of the foundresses of the mission to Selma, Alabama, and a member of the community remarked that she rejoiced that the superior was Emma Chaudet, having known her from St. Michael's. The Selma community was very small, only seven religious, and Chaudet again had multiple jobs: superior, three classes, principal, adult classes, and other initiatives as well! In the very midst of such full activity in Selma, she was called to Paris and told by the superior general, Adele Lehon, that she was being sent back to Grand Coteau as mistress of novices. In 1884, she took up this new apostolate and was revered for her self-discipline, thoughtfulness, and compassion, and for her deep devotion to the Blessed Sacrament.

One novice wrote that the novitiate in Chaudet's time was characterized by obedience, charity, and silence. Chaudet remained superior and novice mistress until 1888; then Grand Coteau became part of the Mexican Vicariate, the American novices went to St. Michael's, and Micaela Fesser was named Mistress of Novices for the remaining Latina novices. Chaudet served as superior of the house at San Luis Potosi, and then returned to Grand Coteau, where she resumed the dual role of superior and mistress of novices from 1892 until the novitiate closed in 1896.

Micaela Fesser, RSCJ

Micaela Ramona Catalina Fesser, born in 183 7 in Cadix, was raised in Havana where her father was Spanish consul. Tutored in the school run by the renowned Purroy sisters (see the section on Cuba), she entered the Society at Manhattanville, received by Aloysia Hardey. After her first vows in 1866, she returned to Havana until profession at Kenwood in 1872. Upon her return to Cuba after making her final vows, she helped in building the school on the Cerro property and the chapel, and was noted for her administrative and organizational abilities. In 1878, she visited the Mother House in Paris, and was allowed to return via Spain to visit her three married sisters. Upon returning to the Cerro, she began construction of the free school, and in 1880 was chosen to be one of the foundresses in Puerto Rico, where she served as superior, Mistress General, and treasurer. She also helped establish a school for black girls, and began retreat work with young women.

Her next assignment was in Guanajuato, Mexico; her stay there, though short, gives evidence of her incredible apostolic energy in organizing groups, teaching catechism, even doing some marriage counseling. Some thirty years after she left, one of her former students showed a portrait of her, calling her the holy Mother. In 1887, she returned to the Cerro in Cuba for a year during which, among other events, she dealt with an epidemic in the school. In 1888, she was assigned to be superior of the house and mistress of the Latina novices in Grand Coteau[iv]; at this point the American novices were sent to St. Michael's. In 1892 Fesser became assistant at St. Michael's, and two years later returned for the third time to the Cerro.

At her fiftieth jubilee many of her former students offered testimonies to her zeal and commitment, especially to the poor. Several of the more touching include these:

Her exterior reflected austerity, but not a severe or narrow-minded austerity, but one serene and youthful, which would radiate her union with Cod and the tenderness of a mother.

And

I remember that one day while she was sick, the doorkeeper came to look for her because of someone in danger who wished to speak to her. That was a resurrection: her face lighted up, her eyes shone, and she got up in a hurry despite her weakness.[v]

…

Emma Chaudet had returned to Grand Coteau as superior and mistress of novices by the time of the closing of the novitiate in 1896 by order of Mabel Digby, superior general, and Jeanne de Lavigerie, vicar of Mexico and the Antilles. This was an exceptionally sad moment. The novice-journalist recorded on September 25, 1896, the reaction of the novices to the announcement:

This day will never be erased from our memories; it will remain written in our hearts. We had a retreat; the first meditation was about sacrifice, the second was about the means to accomplish the sacrifice. In the afternoon, Reverend Mother told us that it was determined by our Reverend Mother General that the novitiate would no longer be here, and that the novices who remained would be sent to the other houses in the following order: Sisters Servin and Azcarate with Mother Arrigunaga to Havana; Sisters Sosa and Camacho to Mexico; Sister Arellano to San Luis and Sisters Josefina Fernandez del Valle and Nadin to Guadalajara. To say what we felt upon hearing this and what we will continue to feel each moment until the hour of departure is impossible for me. It is a mixture of complete voluntary submission to the will of Cod, manifested by our superiors, and the most profound pain of abandoning our beloved novitiate and all it has meant to us.

Apparently the closing represented a new emphasis which referred decisions to the Motherhouse, rather than leave decisions at the local level, as had been Madeleine Sophie's approach with those who founded the American houses. This development may well be seen by future Society historians, as it is presently by Marie Louise Martinez whose painstaking research and prodigious knowledge of this history makes this essay possible, as a moment of retrenchment and Eurocentrism, and a movement away from the international spirit which reigned during these years at Grand Coteau. When such a period ended is a matter of opinion, but it is likely the Chapter of 1970 which, applying the painful lessons of the Special Chapter of 1967, took a much more outward focus in its chapter deliberations than had been possible before, and took decisions (unfortunately translated as options) that restored the international focus not only within the Society, but in its apostolic focus with the world it longs to serve.

Sources

Azcarate, Mercedes, RSCJ. Tradiciones de Familia. Privately printed. [Havana, ca 1922].

Ives, Elizabeth, trans. A Translation of the Memoires of Reverend Mother Tommasini, ts. Manhattanville, 1920. Memoires de la Reverende Mere Maria Stanislas Tommasini: Religious du Sacre Coeur: 1827-1913, ed. Claire Benoist d'Azy RSCJ (Roehampton, 1918).

Journal of the Novitiate, 1873-1896. Written by various novices. Grand Coteau, LA.

Letters from Amelie Jouve to Victoria Martinez, 1867-1879; copies in the national archives.

Martinez, Marie Louise, RSCJ. Notes drawn from Annual Letters and

[i] In Louisiana, parish can mean civil or religious jurisdiction; in this case, it refers to the civil parish, known in other states as county.

[ii] "Some novices, however, were likely to be found in ensuing years at St. Michael's, Bayou Lafourche, and other places in Louisiana, or in the Midwest for that matter, during the period when the two sections of the Mississippi Valley were together in one vicariate.” This observation by Marie Louise Martinez is in a paper situating the various novitiates. She further notes that "this is part of a long and rather complicated story, not to be told here.”

[iii] The author is grateful to Carmen Speets for translation assistance with several sources.

[iv] See Appendix for lists of Latina Novices.

[v] See Azcarate.